You’ve heard of “driving while black.” That’s the police penalty on black motorists, who get stopped, ticketed and searched more often and for flimsier reasons than white drivers.

Then there’s “learning while black, male and with disabilities.”

That’s the trifecta pick for the highest suspension rates in American schools. More than 1 out of 3 such students in middle and high schools were kept out of classes once or more during the 2009-10 academic year, outstripping all other groups, according to The Center for Civil Rights Remedies at UCLA.

Recent reports also have echoed the wide disparities in the ways schools mete out discipline.

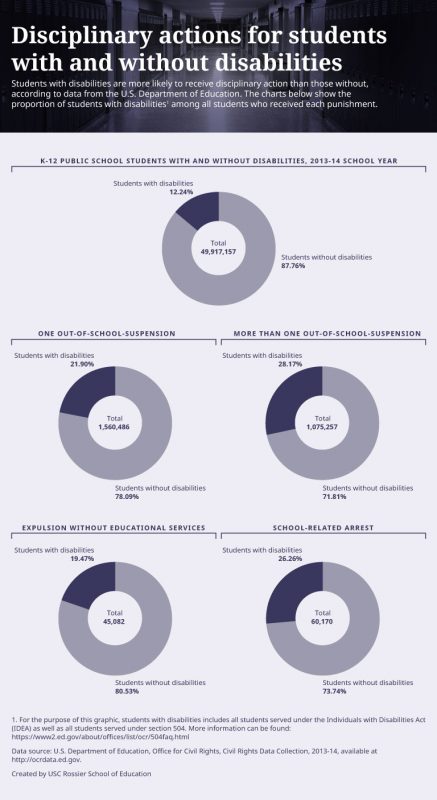

Students with disabilities, including intellectual limitations, ADHD, dyslexia, autism, and impaired hearing or vision, are twice as likely to be expelled or suspended than their non-disabled peers. They also account for a quarter of public-school students who are suspended, arrested or turned over to law enforcement––more than twice their share of the total student population, according to the Government Accountability Office.

Citation for this content: USC Rossier’s online masters in school counseling program

The disproportionate justice is even sharper when divided by race. Twenty-five percent of black boys and girls with disabilities were suspended at least once during the school year. That’s almost three times as often as for white students with disabilities.

Most troubling, punishment rates don’t simply reflect different rates of misbehavior. For example, research shows black male youths are no more likely to be found with drugs, alcohol or weapons at schools than other students yet get suspended far more often.

The toll from the so-called school-to-prison pipeline can be huge and lasting.

“Every time a student is quote-unquote ‘in trouble,’ they’re not learning,” said Alan Green, an associate professor at the USC Rossier School of Education.

What’s more, Green noted in an interview with Michelle Strom for USC Rossier’s blog, kicking students out deprives them of a chance to learn from conflicts and to grow. That’s a core concept behind restorative justice, which calls for treating disruptive students as people, not perpetrators.

Schools have a legal duty to provide a safe place to learn for all students. And violence is a serious concern in some schools. Experts, however, say educators can be too quick to criminalize misbehaviors they can address more effectively with a lighter hand.

A frustrated student with autism or a learning disability who violently acts out in school, for instance, deserves a tailored response instead of the same punishment as a classmate who may be willfully disruptive.

But that deliberate approach is a common casualty in many schools with zero tolerance for misconduct. Look no farther than New York, Chicago or Miami-Dade County—three of the nation’s largest school districts––which have more security officers than counselors.

Expulsions, arrests and other harsh disciplinary actions can set off a chain reaction of woes for students. They’re more likely to be suspended again, graduate later or drop out altogether. Research also suggests booting out disruptive violators may penalize the remaining students and make it more difficult for them to thrive academically.

As lawyer and civil rights advocate Amir Whitaker said in a recent interview with USC Rossier’s blog, it’s time to debunk the notion that schools should “kick out the bad kids so that the good kids can learn.”

Alexis Anderson is a Digital PR Coordinator covering K-12 education at 2U, Inc. Alexis supports outreach for their school counseling, teaching, mental health, and occupational therapy programs.

Sources:

Our authors want to hear from you! Click to leave a comment

Related Posts