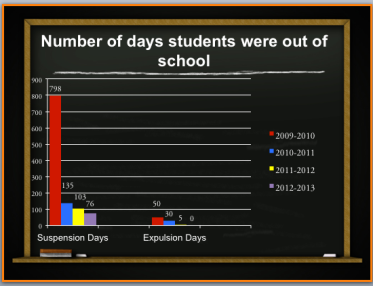

Three years ago, the story about how Lincoln High School in Walla Walla, WA, tried a new approach to school discipline and saw suspensions drop 85% struck a nerve. It went viral – twice — with more than 700,000 page views. Paper Tigers, a documentary that filmmaker James Redford did about the school — premiered last Thursday night to a sold-out crowd at the Seattle International Film Festival. Hundreds of communities around the country are clamoring for screenings.

__________________________________

But many educators aren’t convinced. They ask: Can the teachers and staff at Lincoln explain what they did differently? Did it really help the kids who had the most problems – the most adverse experiences? Or is what happened at Lincoln High just a fluke? Can it be replicated in other schools?

Last year, Dr. Dario Longhi, a sociology researcher with long experience in measuring the effects of resilience-building practices in communities, set about answering those questions.

The results? Yes. Yes. No. And yes.

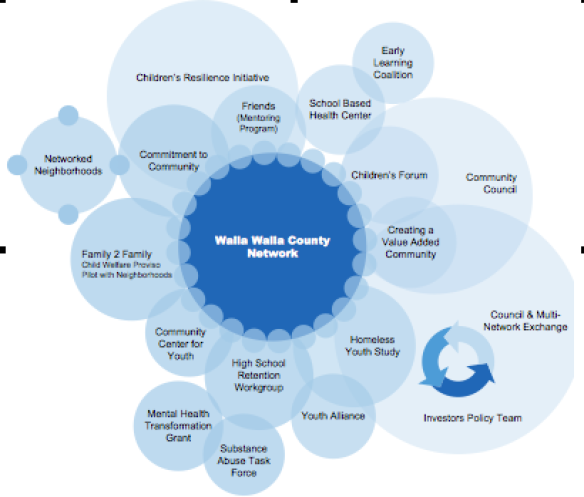

In case you don’t know Lincoln High School’s story, here’s a quick summary: In 2010, Jim Sporleder, then-principal of Lincoln High School, learned about the CDC-Kaiser Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study and the neurobiology of toxic stress. The ACE Study showed a link between 10 types of childhood trauma and the adult onset of chronic disease, mental illness, violence and being a victim of violence. The Children’s Resilience Initiative (CRI) organized the workshop. It’s a community organization in Walla Walla that creates awareness about childhood adversity and encourages all sectors of the community – business, faith-based, corrections, law enforcement, education, etc. — to integrate trauma-informed and resilience-building practices.

Here’s what Sporleder learned:

Severe and chronic trauma (such as living with an alcoholic parent, or watching in terror as your mom gets beat up) causes toxic stress in kids. Toxic stress damages kid’s brains. When trauma launches kids into flight, fight or fright mode, they cannot learn. It is physiologically impossible.

They can also act out (fight) or withdraw (flight or fright) in school; they often have trouble trusting adults or getting along with their peers. They start coping with anxiety, depression, anger and frustration by drinking or doing other drugs, having dangerous sex, over-eating, engaging in violence or thrill sports, and even over-achieving.

With the help of Natalie Turner, assistant director of the Washington State University Area Health Education Center in Spokane, WA, Sporleder and his staff implemented three basic changes that essentially shifted their approach to student behavior from “What’s wrong with you?” to “What happened to you?”

- When a kid showed symptoms of stress, teachers intervened early to provide help – a quick talk, a longer chat with a school counselor, or intervention with a counselor at the adjacent Health Center.

- For behavior that required more follow-up, such as not complying with a teacher after numerous requests, teens talked with Sporleder, who walked them through where they are in their decision-making ability: green, yellow or red. If they’re fuming, for example, they’re in the red zone, are unable to think clearly, need a day to think about things before they can discuss how to handle similar situations differently, and what actions will get them to that point.

- In staff meetings, conversations switched from how to discipline kids to how to help them and their families.

Two years into the new approach, CRI brought in Laura Porter, co-founder of ACE Interface and former director of the Family Policy Council in Washington State, to work with Lincoln High teachers and staff to find out exactly what they were doing differently. They came up with four sets of new, interrelated practices:

- Safety practices – Teachers provided an increased sense of safety to decrease trauma triggers and provided emotionally safe spaces.

- Value practices – Teachers and staff held and expressed values of hope, teamwork, healthy family feeling, compassion and respect; more conversations that matter increased the quality of relationships that reinforced the values.

- Conversation–relationship normative practices – The more “conversations that matter” that took place – the “What happened to you?” conversations — the more descriptions that occurred of behaviors of compassion and tolerance, the more behavioral norms were set and enforced.

- Learning practices – Greater learning occurred due to fewer trauma triggers, generated by a greater sense of safety, due to different values and more ‘conversations that mattered’ between teachers and students, sustained by students’ own reinforcement of different skills and new normative relations.

In Spring 2014, Longhi surveyed 111 students for their ACE scores AND resilience scores, and obtained attendance, grades and test scores from school records. The survey also asked students to reflect on their school and life experiences since coming to Lincoln High. (You can download the report from the Children’s Resilience web site.)

The four types of students’ experiences, related to the practices that teachers and staff put in place, included:

- Learning to trust, confide, be liked and loved.

- Learning to respect themselves and others.

- Learning to be responsible for their actions.

- Learning that others were proud of their academic achievements.

The three dimensions of resilience that increased included supportive relationships, problem solving and optimism.

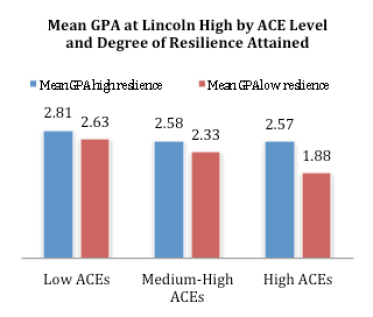

The results? “Resilience trumped ACEs among students who had gained resilience at Lincoln High,” says Longhi. “Resilience completely moderated” the negative impact of ACEs on students’ grades and test scores.

Specifically:

- 72% percent of students with an initial low resilience level improved to average and/or high resilience levels.

- Resilience made a difference even among higher ACE students: Higher resilience students had higher grades for all ACE groups.

- Among low-resilience students, ACEs continued to affect their grades: Students with higher aces had lower grades.

- Among high-resilience students, their ACEs did not impact grades: Grades were high, even for students with higher aces.

This research is an important first step in measuring resilience and evaluating how resilience-building practices can help kids who have high ace scores perform better in school.

To give you an idea of what the differences were between a students who had little or no resilience, and those who had high resilience, here’s a description from the report, in the teens’ own words.

Teens with no or low resilience say:

Yes, I struggle with anger and depression

- all the time – because I deal with it every day and it only gets worse

- I punch walls – punch stuff

- I get mad and want to fight people

- I think and cry – cause I don’t like talking with people

- wWell, I don’t cry, I hold my own… knowing nobody ever cares… really

- I cry or bottle it up and freak out days later

- I smoke weed

- I cut myself

Unable to cope

- I take it out by yelling at my brother

- I just like to have time alone. I’m more of a ‘self-confine’ person – I dislike to tell others about my problems because that would just get them involved

I plan to

- not be a bum

- get a piece of paper that says I am better than the person without it

- leave town

- be homeless

- die by age 20

The teens who have developed high resilience and are thriving say:

In past struggles

- I used to not eat for 4 days at a time

- I was too sad to do anything – felt worthless

- I was always alone — no point in doing things

To better cope

- I was not doing good, but I had great friends to help me get through it all

- I stopped smoking grew better relationship with my family– teachers realized that I was making a change…

The biggest change has been

- my attitude – it has changed since I came to Lincoln – I look forward to every day

- I have become a lot nicer – became close enough to a teacher… to talk about anything

- I know that everyone has their struggles and all it takes is just to reach out to them and let them know it is okay

Positive relations

- the only school that actually accepted me

- being able to change my life with the support of staff – meeting people I wouldn’t think I would have a good relationship with

My proudest moment was

- when I was given support at Lincoln about what I can do – It helped me do more and work harder – to help me raise my GPA

- when I got my grades – I achieved something I never thought I would until I came here

- when I reached out for extra help in math which is something I probably would have been embarrassed about years ago

My school and future plans are

- I want to graduate from Lincoln High School because I have come too far to quit

- I also want to graduate because I can hold that as a memory that I was here as a part of Lincoln.

- yes, graduate, so I can go to a 4 year college, learn more… make it into a career

- I want to eventually get married and have children who will look up to me and be proud — give my children a good role model

But what about the 30 percent of the students for whom the changes at Lincoln made little or no difference?

“I don’t think we can answer that from this work,” says Teri Barila, director of the Children’s Resilience Initiative. She offers an educated guess: “The impact trauma has on creating negative talk, negative scripts, negative outlook, is strong, and helping a student shift from that sense of failure is not easy.”

In the meantime, more schools are implementing trauma-informed practices. With the support of CRI, trauma-informed practices are being introduced in Head Start and elementary schools in Walla Walla. Other schools that are implementing trauma-informed practices include Spokane and Seattle, WA; San Francisco and San Diego, CA; Blaine, MN; and New York City, NY. Jim Sporleder, who retired from his position as principal at Lincoln High School, has been working to help other high schools become trauma-informed.

What’s useful to understand about Lincoln High School ‘s new approach is the context in which it made those changes – in particular, the large role the community played. The Children’s Resilience Initiative and its many partners made a concerted effort to educate the community of Walla Walla about the new knowledge about human development, how punishment really doesn’t help children learn, and how building resilience can give children hope and opportunity. They worked closely with the school to develop supports for students, including after-school classes and special services. The development of the Health Center, the clinic adjacent to the school, was the result of a community effort.

Barila and Longhi recently presented a strategy paper to Walla Walla school administrators. In it, they say:

Research shows that starting earlier, at younger ages, with trauma-informed practices in schools, with community-wide supports, leads to better results….Adding new programs focused on students may not be enough to break the intergenerational cycle of ACEs. Breakthrough impacts…can only come from collective impacts of changes in adult caregivers, including teachers and parents, and in the communities where students live.”

Written By Jane Ellen Stevens

Resilience practices overcome students’ ACEs in trauma-informed high school, say the data was originally published @ ACEs Too High » Jane Ellen Stevens and has been syndicated with permission.

Sources:

Our authors want to hear from you! Click to leave a comment

Related Posts