In 2009, when the Kings Canyon Unified School District in California’s rural Central Valley offered its 19 schools the opportunity to adopt a system that would reduce school suspensions and expulsions, Reedley High School jumped at the chance.

Today, Reedley is in its fourth year of changing a zero-tolerance policy that has failed this school and community miserably, just as every zero-tolerance policy across the country has. The school, which has 1,900 students, is feeling its way out of those draconian days by integrating PBIS — Positive Behavioral Interventions and Support — and entering into a unique partnership with the West Coast Mennonite Central Committee and the local police department to implement a successful restorative justice program.

This approach is already having remarkable effect. The school saw a 40% drop in suspensions from the 2010-2011 to the 2012-2013 school year — from 401 to 249 suspensions involving 198 and 80 students, respectively. Expulsions went from 94 in 2010-2011 to 20 last year. But this year’s trends indicate that impressive decline may have stalled out.

Although everyone interviewed for this story – including the principal, learning director, and a teacher — says that suspensions don’t work, Reedley is still stuck with a harsh suspension policy that the district and the school board have barely loosened. Although the district was forward-thinking enough to support program changes and the school is beginning to deliver, like any entrenched system, the old ways of discipline pull hard against change, even if the data and the science that show the old ways damage kids are indisputable.

“It’s been a journey,” says Mary Ann Carousso head of student services. “We’re taking it in pieces.”

___________________________

The sprawling Reedley High School campus includes an auditorium, library, and five hexagonal and several rectangular rows of classrooms around a large two-story building. On a clear winter day, the snow-capped Sierra Mountains form a stunning backdrop. As in most large high schools, adults barely corral the high-octane teen energy that erupts across the plaza between classes, and struggle to ignite and channel it during classes. The school draws as many students from the city of 25,000 as it does from the agricultural farming country it serves – nearly 80% are Latino, 16% are white, 1.5% are Asian, 1% are Filipino, and 0.7% are African-American. About 65% come from families that live just above, at, or below poverty level. The nearest city, Fresno, is 25 miles distant and worlds away.

Like most school districts in California, Kings Canyon adopted a zero-tolerance policy in the late 1990s. Just one year after the U.S. Congress passed the Gun-Free Schools Act of 1994, the adoption of broad zero-tolerance policies spread like a virus across the United States. Once zero tolerance was locked in, school boards, districts, teachers and principals warped it, some say, by the pressure to perform well on tests. Kick the troublemakers out, and there’s less disruption and interruption in class.

But in the mid-2000s, data began showing that zero tolerance wasn’t working. In fact, it was shunting kids into a school-to-prison pipeline that disproportionately targets minorities. The research, the U.S. Office of Civil Rights and the American Civil Liberties Union convinced people at the Fresno County Office of Education to look for alternatives for its 32 districts, which include Kings County.

“The research was constantly telling us that even one suspension could put a kid down a path we don’t want them on,” says Carousso. Providing reports to the U.S. Office of Civil Rights and being watched by the ACLU also put Fresno County on notice. “Even though I’m not always glad of it,” Carousso says of the ACLU, “they point out things we should be aware of.”

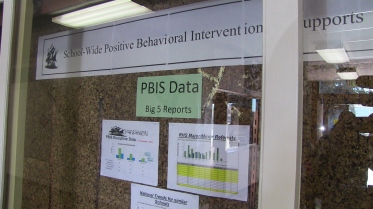

The program that Fresno County settled on was PBIS, which is used in more than 20,011 schools nationwide; more than 700 of those are in California. In essence, says Carousso, PBIS helps the entire school system — teachers, administrators, janitors, bus drivers, cafeteria workers — “set up kids for success first, instead of ‘gotcha’. It sounds hokey. It sounds corny.” But it works…to a point.

Kings County Unified implemented the PBIS system a few schools at a time; the last group started the three-year transition this year. “We decided to start slow and roll it out in groups of schools, and let other schools watch the success,” says Carousso. “Reedley High stepped out first. The need is big at this school.”

When Reedley High School Principal Rodney Cisneros first arrived at Reedley in 2002, “kids were out of this place left and right,” he recalls. “We’re supposed to help kids stay in school. Before, we made a lot of assumptions about kids — that they know what to do. But they don’t always know. They’ve got to be taught.”

__________________________

At the essence of PBIS is the understanding that to change students’ behavior, you have to start with the teachers, staff and administrators. “We’re changing the behavior of the adults on campuses,” says Carousso, “and teaching them how to respond to poor behavior on the part of kids. It’s all so simple and logical. But it’s a lot of work, and it’s a huge commitment.”

PBIS isn’t a program that’s an add-on, says Rob Horner, co-director of the U.S. Department of Education Technical Assistance Center on PBIS. It’s a framework that’s integrated into every aspect of the school: in the classroom, in the hallways, in the lunchroom, on the playground. Kids are told what behavior is expected from them, they’re praised and rewarded for it, there’s a game aspect to it to make it fun, and the rules are the same in every classroom. Or at least that’s the theory.

____________________________

Before the start of the 2009-2010 school year, Learning Director Joseph Arruda took a team of 17 people through four workshops with trainers from Orange County. These 17 people met monthly to hammer out how PBIS would be implemented at Reedley and then educated the other staff about the system.

The first year, says Cisneros, was focused on “just getting a lot of staff on board, and laying the foundation and a vision.”

They used the initials of Reedley High School to come up with a vision: Respect for self, others and surroundings. Honorable to self and others. Success to all.

____________________________

During the second year, the entire complement of 76 teachers learned how to teach the students what the expectations were for their behavior in the classroom, in the cafeteria, outside classrooms, and at sporting events. Arruda set up the system to collect data on referrals, and established baseline numbers.

During the third year, the 2012-2013 school year, the recognition piece — for students and teachers — was implemented. “If kids are displaying characteristics we’re looking for, we recognize and honor those kids and teachers,” says Cisneros. Teachers can reward students with pirate bucks (the Reedley mascot is a pirate), which enters them in drawings for gift cards for Jamba Juice, McDonald’s Starbucks, and a local pizzeria. Kids can nominate teachers to be “captain of the ship” for a month.

The school began using the PBIS data system in 2011-2012. You could say data are the PBIS sweet spot. “The data speak volumes,” says Arruda.

Because each student referral is noted with the type of infraction, the time it occurred and its location, the data opens a brand new window onto student and teacher behavior. Students who have the most referrals are provided additional help, including regularly touching base with a teacher or counselor. Their progress can be tracked to determine if more services are necessary. Arruda can identify places and times on campus where an adult presence would keep kids from acting out. And, administrators can see that kids are being referred more often from one teacher than another.

“We show the staff the data,” says Cisneros. “We can help the teachers who have the highest referrals with strategies they can use in their classrooms.”

_________________________

Referrals are usually the first step in the process of being suspended or expelled. They’ve dropped nearly 50%, from 2,045 in 2011-2012 — when skipping class and dress code violation were at the top of the list of infractions — to 1,174 referrals last year. Over the last two years, three categories of defiance and disruption comprised 64% of all referrals. This year, the number and types are trending to be about the same as last.

Most of the referrals – a good 75 percent – come from classrooms, so it’s no surprise that the biggest challenge in this transition to a more positive school environment has been some of the teachers.

It took some time for the 76 teachers at the school to embrace the change. During the 2012-2013 school year, about 80 percent were on board. That’s increased to 98 percent this year, says Arruda. The teachers who are most skeptical are some 20-year veterans who don’t believe that disciplining kids is their responsibility. If students misbehave, these teachers want to eject them from class immediately and send them to Arruda.

“In the past, their way is to just get rid of the problem,” he says. “But the amount of time it takes for a learning director to see a student equals time away from the classroom, and that student is missing out on instruction.”

This year, Arruda was hoping to see the school continue its success in reducing suspensions and expulsions. But the first semester’s numbers haven’t changed much since last year’s. So, he’s ramping up the PBIS support systems for students who are still struggling with their behavior in class. This includes counselors who work with students to develop a behavior plan, and requiring students to participate in a check-in/check-out program in which each student meets with a staff member in the morning and at the end of the day to talk over the day and to review their behavior scorecard.

English teacher Arnulfo Sanchez was an early supporter of PBIS. In this class, he’s teaching students how to write about their goals.

____________________________

But, to make the numbers continue their slide, it’s the teachers who may need more tools than PBIS has to offer. (Also, the school district has to loosen its grip on school discipline — more about this later).

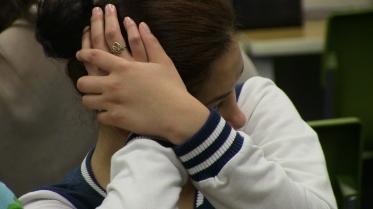

Many educators still think kids’ “bad” behavior is deliberate, and that the kids can control it. But it’s often not, and they can’t – not without help, says Dr. Joyce Dorado, director of HEARTS — Healthy Environments and Response to Trauma in Schools, and associate clinical professor in the University of California San Francisco Department of Psychiatry, Child and Adolescent Services. Their behavior is a normal response to stresses they’re not equipped to deal with, she explains. Their behaviors make sense if they’re jumping in to defend their mother from an alcoholic raging father, or are responding defensively to a parent who continuously screams at them. But when the raised voice of a teacher or a counselor who’s criticizing inadvertently triggers the same response, these behaviors look “abnormal, rude, or inappropriate,” says Dorado. “So, they’re getting kicked out of class and disengage from school. That puts our kids at incredible risk for later problems, including imprisonment.”

In fact, serious, chronic childhood trauma is so common that two-thirds of U.S. adults have experienced at least one type out of ten measured by the CDC’s Adverse Childhood Experiences Study (ACE Study). These adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) include physical, sexual or verbal abuse; physical or emotional neglect; and five types of family dysfunction — family violence, living with alcoholic (or other drug-addicted) or mentally ill parents, losing a parent to divorce or abandonment, or a family member who’s in prison.

And almost half the nation’s children under the age of 18 have experienced at least one or more types of serious childhood traumas, as measured by a recent survey on adverse childhood experiences by the National Survey of Children’s Health (NHCS). This translates into an estimated 35 million children nationwide. (Since parents responded to the survey, questions about physical, sexual and verbal abuse were excluded, since it was unlikely those would be answered accurately. Hence, 35 million children suffering childhood trauma is on the low side.)

Dorado says it’s important for teachers to become “trauma-informed” – that is, to learn about the effects of ACEs and to receive training in how to work with children who’ve experienced or are experiencing trauma. That’s because the toxic stress caused by trauma can damage children’s brains, including the brains of teens, explains Dorado, making them susceptible to being triggered into “fight, flight or freeze” mode, even when they aren’t actually being threatened. As a result, they can have trouble concentrating, learning, or sitting still. At the slightest trigger – a teacher yelling at them or another student accidentally knocking into them — they can erupt into rages, lash out at others or hurt themselves. Or they can withdraw in fear and not participate in anything that’s going on around them. None of this behavior is intentional, says Dorado.

Trauma-informed practices are the foundation for, but are not meant to replace other frameworks such as PBIS, Safe & Civil Schools, or restorative justice, says Dr. Christopher Blodgett, director of the Washington State University Area Health Education Center, whose research shows a direct link between ACEs and academic failure. Becoming trauma-informed not only supports those approaches, it’s the bedrock for all of them, he says. And, in fact, schools in Spokane, WA, and Brockton, MA, that use PBIS have integrated trauma-informed practices.

There’s another reason trauma-informed practices work especially well with other positive behavioral approaches such as PBIS or restorative justice. The neurobiological effects of toxic stress have shown that school discipline is a health issue, not just a behavior issue. While one teen suffering toxic stress may scream and throw chairs in a “fight” response to a trigger, another will curl up and withdraw in “flight” or “fright”. These kids are often labeled as “lazy”, “slow learners”, or “unmotivated”. They slip through the PBIS or restorative justice net because they never act out: They just sit quietly at their desks and never speak. But they disconnect and fall behind, just as those who are suspended and expelled do, and are likely to drop out of school.

_______________________

Last year, Reedley High School added a restorative justice program to its efforts to reduce suspensions and expulsions. Essentially, it’s a campus branch of the Reedley Peace Building Initiative. The West Coast Mennonite Central Committee (MCC) and the Reedley Police Department launched the program in Reedley in September 2011. Led by Lt. Marc Ediger, the program gives youth arrested on misdemeanor charges (vandalism, graffiti, minor fights and possession of drugs) the option of participating in a restorative justice program instead of entering the juvenile justice system.

“We modeled our program on the Fresno Pacific University Victim Offender Reconciliation Program,” says Swenning. Fresno Pacific, founded by the Mennonites, is where Ron and Roxanne Claassen, leaders in restorative practices for education, do their work.

“The youth have to admit to what they have done, show some remorse, and show initiative to take responsibility,” says John Swenning, the MCC restorative justice program coordinator and a 15-year veteran of law enforcement. “Then we allow them to go through the program.”

The victim and the offender enter mediation with one of the community’s 40 volunteer mediators. An agreement is worked out, and victim and offender agree to do whatever both sides feel is just for their crime, says Swenning.

“It can be something as simple as an apology letter. If there’s damage — graffiti or a stolen cell phone — then the offender may pay restitution for losses. A big part of this is community service — not just raking leaves, but getting involved with community. Several businesses, churches, and city departments provide opportunities for offenders to work with folks in the community.”

During the first year, 50 juveniles went through the program, says Swenning. That’s 50 who did not enter the juvenile justice system, he points out. “We’d like to handle 100 percent of the juvenile crimes,” he says. “We’re pretty close to that now.”

“Success in the school program is even greater,” says Swenning. In the two semesters – spring and fall — of 2013, 50 students went through the program. “We could’ve done more than that. We had more incidents. But with our resources, that’s all that we could handle,” he says.

Most of the cases involved students who were caught with marijuana or were fighting. Unlike the city program, which offers restorative justice as an alternative to punishment, all of the students are suspended or expelled prior to participating in the school restorative justice program.

Reedley High School students are automatically suspended for five days if:

- they get in a physical fight with another student;

- they smoke marijuana, drink alcohol or do other drugs on campus;

- come to school under the influence of marijuana, alcohol or other drugs;

- if they use profanity with an adult (depending on the severity);

- vandalize school property;

- if willful defiance escalates into abusive language or threatening behavior, as defined by a teacher;

- are caught stealing.

Students gather to watch two girls get in a fight. They were marched to the principal’s office and then escorted off campus.

For other offenses, punishment varies. The first time kids get in a verbal tussle, instead of receiving an automatic three-day suspension, they now have the option of taking part in a mediation in which they agree to resolve their dispute and sign a contract to promise to refrain from yelling at another student. However, they are automatically suspended for three days if they break a conflict resolution contract by engaging in a verbal fight.

Behaviors such as “ordinary” defiance, disruption, disrespect, inappropriate language, and harassment, fall into the referral category. Five referrals, and they’re suspended.

Students are expelled if they bring a weapon (a knife or gun) to campus or sell drugs, or if they’ve been previously suspended and this is their second suspension.

Students who are repeatedly expelled can be sent to a county Community Day School operated by the Fresno County Office of Education, says Carousso. Others may be sent to an alternative school on a probation basis, or required to do home study. Some may enter a limbo called suspended expulsion, which requires them to be out of school for a semester or a year while they engage in a restorative justice contract. A parent must apply to the district to have the student readmitted.

Reedley High School Principal Rodney Cisneros (l) and Learning Director Joseph Arruda (r) take a walk through the high school’s commons during lunch.

__________________________

Over the last three years, the district has relaxed – slightly — its school discipline policy. Besides eliminating automatic suspensions for kids having verbal fights with each other, they’ve also stopped expelling kids for substance abuse. Instead, teens receive an automatic five-day suspension and, after they return to school, have the option of entering a substance treatment program the school provides for free. Arruda says 33 students are enrolled in the program.

But the district hasn’t gone as far as some other districts and schools, where trauma-informed systems have been put in place to train teachers to recognize signs of toxic stress and intervene early. In some of these schools, suspensions have been eliminated altogether, and expulsions have dwindled down to a handful. Nor has the district decided to ban suspensions for “willful defiance”, as Los Angeles Unified School District did in May 2013.

“I’d love to get rid of suspensions,” says Swenning. “But I don’t see that happening. However, I do see giving the kids a choice – participate in restorative justice or be suspended. But I don’t know if the district is there yet. Some day. We’ve got to do something different. What we’ve been doing is destroying us.

“During this time of life for these kids,” he continues, “their brains are all over the place. They do stupid things. It doesn’t mean that they’re bad kids. Ninety-nine percent of the kids want to make things right. They want to make a better life for themselves. We just need to help them through that whole process of growing up.”

Arruda agrees. “I believe that there’s no such thing as a bad kid – just bad choices,” he says.

This is part of an investigative series into “right doing” – how some schools, mostly in California, are moving from a punitive to a trauma-informed approach to school discipline. The series includes profiles of schools in Le Grand, Fresno, Concord, San Francisco, Los Angeles, Vallejo, and San Diego, CA; and Spokane, WA, and Brockton, MA. The series is funded by the California Endowment.

Written By Jane Ellen Stevens

At Reedley (CA) High School, suspensions drop 40%, expulsions 80% in two years with PBIS, restorative justice; but going the distance might require… was originally published @ ACEs Too High » Jane Ellen Stevens and has been syndicated with permission.

Sources:

Our authors want to hear from you! Click to leave a comment

Related Posts

I have always been impressed with the Social Justice work done at Fresno Pacific University and have participated in some of their seminars on Restorative Justice and Conflict Resolution. Around the time that the Reedley High school project was beginning I was in the middle of conducting research on “Searching for Social Justice in the San Joaquin Valley of CA” … And, this article demonstrates that it can be found … something I was unable to do further North of Fresno, CA See: link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1007%2F978-94-007-6555-9_38.pdf