Not every issue of morality that we are faced with is easily discernible— with an easily ascertainable correct action. Many of these issues are nuanced and multifaceted, affecting every person differently and involves a weighing process between imperfect alternatives.

Not every issue of morality that we are faced with is easily discernible— with an easily ascertainable correct action. Many of these issues are nuanced and multifaceted, affecting every person differently and involves a weighing process between imperfect alternatives.

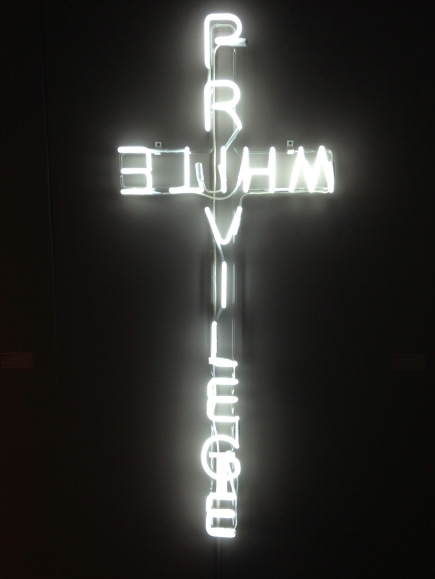

One of those issues is race or ethnicity and furthermore the perceptions and assumptions that come hand in hand. Race and racial prejudice are intricately woven into the fabric of American history. While the most prominent struggle between Whites and Blacks is entrenched in the legacy of slavery, another more subtle battle persists. This battle, in my personal experience, blurs the line of ethical and moral behavior in many settings; particularly social and business relations. This struggle is the plight of those who pass for another race– specifically those non-Whites who may be perceived as White, such as myself. This presents a unique moral and ethical challenge: having to toe the line between my ‘by chance’ white privilege and allegiance to my ethnic background.

Often the struggle to which I refer is given the name of , in which light skin tones are preferred and fare better in arbitrary categories when compared to darker skin tones. There is this persistent trend; according to the historical record that having lighter skin regardless of your racial or ethnic origin is a good thing— a door opener if you will. For fair-skinned Latinas like myself, the identifier of white is available to me, but it comes as a powerful oxymoron to define myself as a white-Latino. The rich history of Latino and Hispanic people is tinged with repression and marginalization, while placing white race as the perpetrators of that oppression, laden with privilege from the get-go. There are many studies, both scientific and academic, exhibiting the inherent ‘benefits’ of white-passing not limited to better marriage prospects, better socio-economic standing, and better employment opportunity only in correlation to having lighter skin regardless of any other identifying factors including gender or age. In my own experience, the vast majority of people who are not Hispanic or Latino themselves believe that we are to a certain extent homogenous: small in stature, darker in tone, with straight black hair. When one do es not fit into the cookie cutter mold that has been cast, there is a sequence of events that can only be described as unsettling to the receiver. At first, there is the glossing over of who you are to accept your external whiteness at face value, allowing you to race-pass should you choose to. Then, should your true ethnicity become known; there is always disbelief or a shot taken at your credibility—somehow you must not know what you’re talking about or you must really be from somewhere else. In my case, I am privileged by my skin color and I have had to learn to navigate a world that consistently mistakes me for something I’m not and only accepts me based on that misconception.

es not fit into the cookie cutter mold that has been cast, there is a sequence of events that can only be described as unsettling to the receiver. At first, there is the glossing over of who you are to accept your external whiteness at face value, allowing you to race-pass should you choose to. Then, should your true ethnicity become known; there is always disbelief or a shot taken at your credibility—somehow you must not know what you’re talking about or you must really be from somewhere else. In my case, I am privileged by my skin color and I have had to learn to navigate a world that consistently mistakes me for something I’m not and only accepts me based on that misconception.

I am the color that white people want me to be, but I am not the person they want me to be nor do they want to be me. It is often just the literal color of my skin that makes me appealing to them. Being labeled as white is problematic because identifying as white ignores all of the struggles that my ancestors went through, and because quite simply, I do not fit into the overarching white historical narrative. My people’s genesis is not located in that kind of whiteness. Often, discerning that I am not actually white is greeted with a sense of unsettlement, like I have somehow upset the natural balance. Colorism can be fickle that way. To offer a small social example, I’ve had others approach me and inquire as to how I keep just the perfect tan over the winter months. The first time this occurred I could not have been older than eleven or twelve. For me, the question did not even make sense because I was not “keeping” a tan—I was not doing anything to my skin, that was just the color that it always was, and I did not know how to respond. Do I admit to being Latina? Do I declare that my unique tone is the physical enduring evidence of the rape of indigenous Puerto Rican women long ago until the blackness faded from my family tree to create me? Do I laugh and play it off? The moment that I own up to being Puerto Rican, the admission is accompanied by varying levels of disbelief, demands for explanations (as if this was really some method designed to hoodwink them!), and requests to speak Spanish as if I need to prove who I am.

People do not like hearing that the preconceived notions they have developed are wrong, especially if they hold unfavorable points of view toward races associated with dark skin tones. This unsettlement can especially manifest itself when expanding business or social circles. I once sat in a job interview for close to half an hour until the manager realized I was not white like her and there was a definite downturn in her attitude toward me—the disappointment in my non-whiteness was palpable. I could not relate to the plight of going on vacation to Mexico and not understanding the natives and getting sunburned. It was almost as if she took personal offense to me severing the imaginary link she had formed between us, like I had deceived her by presently outwardly as a white woman. For her, the idea of who she wanted me to be was preferable to reality.

This extends further into my working experience, where my first name does not betray my Latino lineage but my last name does, leading me to have ‘fooled’ coworkers and managers that assumed me to be white and thus bestowed the ever complicated benefits of white privilege on to me. This is just one instance of the ethical crossroads I find myself at because of the presumptions of others before I have had the chance to self-identify. Working at a sports arena, I have never had my bag searched upon entry, but my ‘brown’ friends have frequently and I am acutely aware that if I wasn’t naturally fair with blonder hair and green eyes things may be different. I once had a fellow Latina coworker, darker skinned then me, tell me that I was only made the team lead during a high profile event because I had a white name and white features and thus would appeal more to the visiting corporate management. In hindsight, she may have been correct.

I live in a culture that values whiteness, even my imperfect whiteness, and seeks to assign privileges to that whiteness that I cannot morally accept. Ethically, I cannot disown my race when it suits me, or when I am hyperaware that my Latino brothers and sisters are victims of colorism that I escape by the happenstance of less melanin in my skin. I cannot stand by the fact that my whiteness means I will not get followed around a store, but my younger brothers will, or that my hair is enviable and my sister’s is unkempt and coarse. My whiteness is a product of history, where colonialism swooped in and somewhere along the line decided that white triumphed over brown. Even more down the line, it mixed with brown enough to create people who look like me: just white enough to be tangentially accepted so long as one plays the part well enough to go undetected. However, I do not want to be accepted that way— to turn one’s back on their identity is to turn one’s back on the heritage, culture, and history that informs the collective identity of all one’s people.

By Jade Reyes

Written By Fordham University Center for Ethics Education

Jade Reyes ’17 is a student at Fordham College Lincoln Center. She is majoring in Political Science.![]()

Incidental White Privilege was originally published @ Ethics and Society and has been syndicated with permission.

Sources:

Our authors want to hear from you! Click to leave a comment

Related Posts