In a video on the Resilient KC website, police officer Mikki Cassidy notes that “my regular day is everybody else’s worst day.” Then she describes how mindfulness training has helped her find peace amid the clamor: “This moment, right here, I’m okay.”

Later in the clip, Sonia Warshawski, a Holocaust survivor, recalls being shoved onto a train to Treblinka and, later, losing her mother to the gas chamber. “One of my highest points is when I speak in schools, when students tell me, ‘You changed my life,’” she says.

And Josiah Hoskins, a youth raised in foster care, talks about the mantra that helped him survive: “Even if all you have is yourself, with a wall behind you and the world coming at you, you can make peace with yourself.”

The video concludes with four words—“Stories Matter. What’s yours?”—and an invitation for others to share experiences of adversity and healing.

Awareness on Both Sides of the State Line

The campaign is just one prong of Kansas City’s multi-sector effort to raise awareness about adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) and build resilience on both sides of the state line. Resilient KC — a partnership between the pre-existing Trauma Matters Kansas City (TMKC) network and the Greater Kansas City Chamber of Commerce — has worked to cultivate “ambassadors” who can bring the ACEs message to colleagues, clients and community members in business, the armed services, education, justice and health care.

ACEs are adverse childhood experiences that harm children’s developing brains so profoundly that the effects show up decades later; they cause much of the U.S. and the world’s chronic disease, most mental illness, and are at the root of most violence.

The CDC-Kaiser Adverse Childhood Experiences Study (ACE Study), a groundbreaking public health study, discovered that childhood trauma leads to the adult onset of chronic diseases, depression and other mental illness, violence and being a victim of violence.

The ACE Study looked at 10 types of childhood trauma: physical, emotional and sexual abuse; physical and emotional neglect; living with a family member who’s addicted to alcohol or other substances or who’s depressed or has other mental illnesses; experiencing parental divorce or separation; having a family member who’s incarcerated, and witnessing a mother being abused. Other subsequent ACE surveys include racism, witnessing violence outside the home, bullying, losing a parent to deportation, living in an unsafe neighborhood, and involvement with the foster care system. Other types of childhood adversity can also include being homeless, living in a war zone, being an immigrant, moving many times, witnessing a sibling being abused, witnessing a father or other caregiver being abused, involvement with the criminal justice system, attending a zero-tolerance school, etc.

The ACE Study found that the higher someone’s ACE score – the more types of childhood adversity a person experienced – the higher their risk of chronic disease, mental illness, violence, being a victim of violence and a bunch of other consequences. The study found that most people (64%) have an ACE score of one; 12% of the population has an ACE score of 4. Having an ACE score of 4 nearly doubles the risk of heart disease and cancer. It increases the likelihood of becoming an alcoholic by 700 percent and the risk of attempted suicide by 1200 percent. (Here’s more information about ACEs science. Got Your ACE Score? ….and resilience score.)

Since Fall 2015, Resilient KC has participated in, and received two years of funding from, Mobilizing Action for Resilient Communities (MARC) grant, funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and administered by the Health Federation of Philadelphia. Thirteen other communities also participate in MARC.

“We’ve always had people who are interested,” said Marsha Morgan, who helped launch TMKC while working as chief operating officer of Truman Medical Center’s department of behavioral health. “But now we’re seeing real levels of commitment.”

The MARC grant, she said, prodded TMKC to clarify its focus and establish a 20-member steering committee, with work groups focused on each of the network’s target audiences.

Last fall, the network launched a learning collaborative. The goal was to find ten organizations that would pledge to be part of a year-long learning process; they got commitments from fourteen. A local television station recently agreed to promote stories of resilience. “And we have foundations now saying, ‘This is a priority,’” Morgan said.

A Growing Network

Resilient KC’s website, which includes a calendar of community events such as a dinner with Shaka Senghor, author of Writing My Wrongs: Life, Death, and Redemption in an American Prison, also has links to an ACE survey (the questions from the Anda/Felitti study with additional queries about racism, bullying and neighborhood violence, borrowed from the Philadelphia Expanded ACE Study) and a resilience questionnaire. So far, more than 1,000 people have taken the survey; Morgan hopes that number will grow to several thousand before TMKC analyzes the results in May.

Resilient KC and Youth Ambassadors presented an inspiring community dinner with keynote speaker Shaka Senghor. Photo: Kyle Rivas.

The network has welcomed the first glimmers of interest from members of the faith community, Morgan said, along with unexpected partners such as the Kansas City Royals and first responders: police, emergency workers and 911 dispatchers. Police Captain Darren Ivey, who leads the department’s office of diversity affairs, has become a tireless champion, helping to design a training on vicarious trauma and mindfulness that has reached 850 people so far.

The local arts community, including ArtsTech, an enterprise and education center for at-risk urban youth, has also yielded uncommon partners. At Resilient KC’s kick-off event in April 2016, ArtsTech students were hired to design chalkboards on which attendees could complete the phrase, “What makes me resilient is…”

Continuing Outreach

Other sectors, including the armed services and regional health centers, have proven harder to reach. Health care providers sometimes protest that “we’re too busy” or “if we open this up, where is it going to take us?” Morgan said. And while Jasmin Williams, program coordinator for Resilient KC, has reached out to large corporations (purposefully using business-friendly terms such as “chronic stress” rather than “trauma”), the initiative has yet to bring small businesses into the fold.

“How do we talk to the restaurant owners, the beauticians and barbers, the hotel people? How do we bring healing habits to them?” Morgan wonders. She’d like to see universities incorporate ACEs and self-care practices into their freshman-year courses on effective study habits; ideally, ACEs and resilience would be woven into the curricula of graduate schools in education, social work and health care.

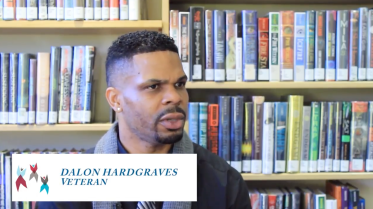

Veteran and teacher Dalon Hardgraves wrote a book “Little Boy Named U” to help kids who struggle as he did.

“One of the biggest challenges is time. People’s busy-ness,” she says, along with the logistics of a Chamber of Commerce partnership that, while enthusiastic and dedicated, also calls for deft navigation of a longstanding bureaucracy.

Moving Forward

Morgan is looking to the future when TMKC will need to decide whether to become its own non-profit organization, institute membership dues or partner with another group that shares its vision.

“What matters is that we stay focused on the vision and mission of what we’re trying to do,” Morgan said—which includes connecting interested audiences with regional experts in ACEs/resilience, advocating for trauma-informed policy at the local, state and national levels, remaining a presence at community events and health fairs and continuing to share stories that embody Resilient KC’s motto of “Thriving Through Adversity.”

She tells of visiting her granddaughter’s elementary school classroom, which houses a “comfort corner,” a table with four exercise balls for kids who need repetitive movement as they work and a rug where children can gather. “When I hear schools say that they’ve named their in-school detention teachers ‘empowerment coaches’ and are working with students so they can recognize what triggers them and practice different ways to respond, I know this work is important.

“What we want to convey to people is: You can move forward. You’re not sentenced to a life of doom because you’ve had these things happen to you…I found a quote recently: Data persuades and stories inspire. People want data, and I remind them that we need it, but we also need to remember our stories.”

Mobilizing Action for Resilient Communities (MARC) is a learning collaborative, coordinated by the Health Federation of Philadelphia with support from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and The California Endowment, of 14 communities actively engaged in building the movement for a just, healthy and resilient world.

This article was originally posted April 7, 2017, on marc.healthfederation.org and is part of a series of community profile updates written by Anndee Hochman, a journalist and author whose work appears regularly in The Philadelphia Inquirer, on the website for public radio station WHYY and in other print and online venues. She teaches poetry and creative non-fiction in schools, senior centers, detention facilities and at writers’ conferences. ![]()

Greater Kansas City first responders, educators, health care workers, sports & faith community embrace learning about childhood trauma, practicing… was originally published @ ACEs Too High and has been syndicated with permission.

Sources:

Our authors want to hear from you! Click to leave a comment

Related Posts